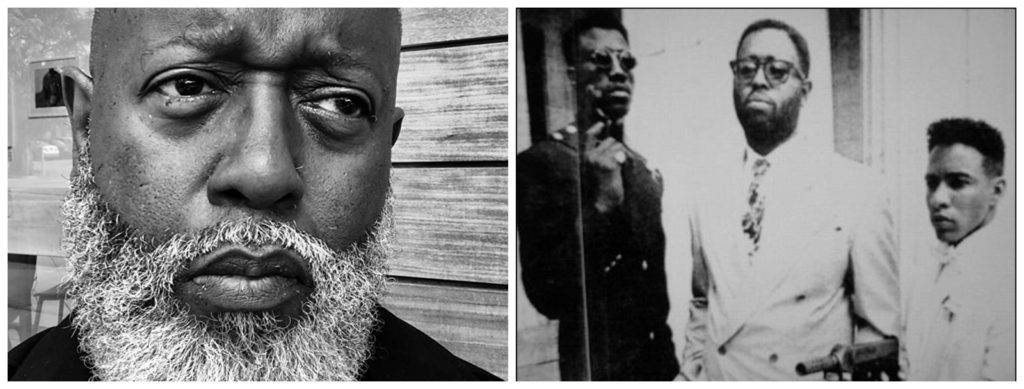

Njs4ever.com is saddened to report that cultural critic, journalist, and filmmaker Barry Michael Cooper passed away on 1/22/25. This interview with Barry that took place in February 2006 is being reposted. His importance to the impact of New Jack Swing cannot be overstated. May Barry Michael Cooper rest in perfect peace.

Below is our interview as originally presented in 2006:

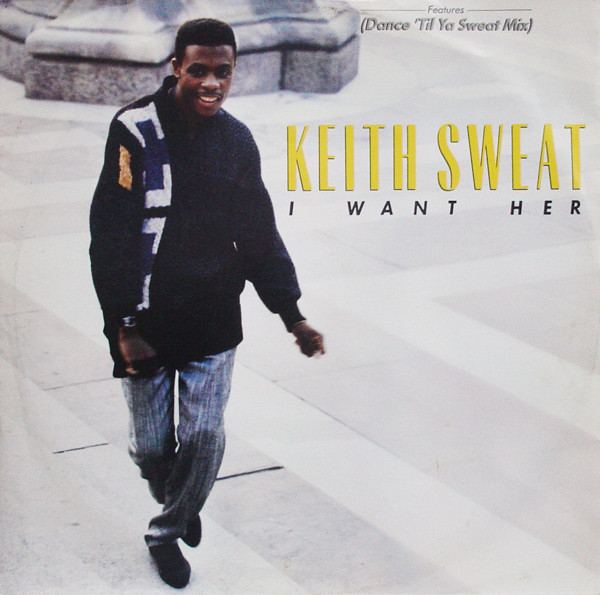

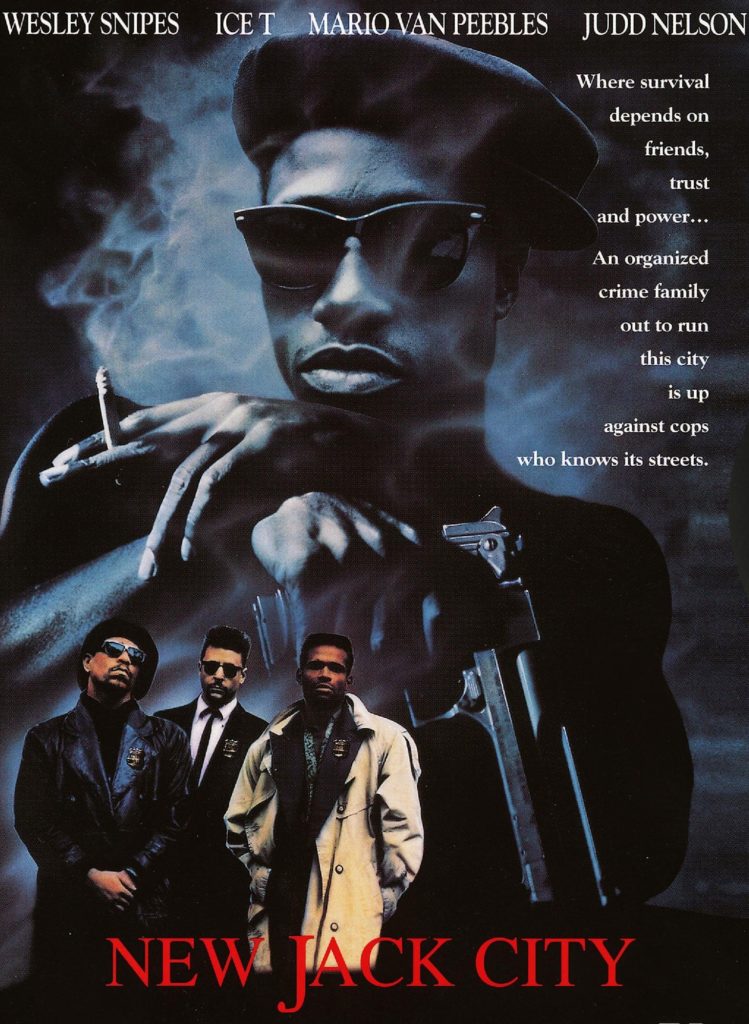

Before jumping off into this interview, I feel it is important to make a proper introduction. I suppose the most relevant point I can drive home again and again is that there would be no genre called “New Jack Swing” without this man. No song called “New Jack Swing” by Wrecks’ N’ Effect. No movie called “New Jack City,” a project responsible for songs like “Let’s Chill” by Guy (the original wedding scene song), “There You Go Telling Me No Again,” by Keith Sweat and that huge no #1 smash from 1991, “I Wanna Sex You Up.” No breakthrough roles for Wesley Snipes, Chris Rock and Ice-T. And certainly no Njs4ever.com for that matter!

Interviewing Barry Michael Cooper – a respected journalist and a trailblazer for most, if not all hip-hop journalists who follow him, was an incredible experience. I cannot emphasize how important this moment has been for NJS4Ever. We promised 2006 to be an even bigger one than 2005 when we established contact with Teddy Riley himself, and so far things are looking good. Enjoy this interview – there’s a lot to learn.

NJS4E: What is the etymology behind the term New Jack Swing?

BMC: That’s a really good question. There’s a good answer to that, and a lot of it is not musical.

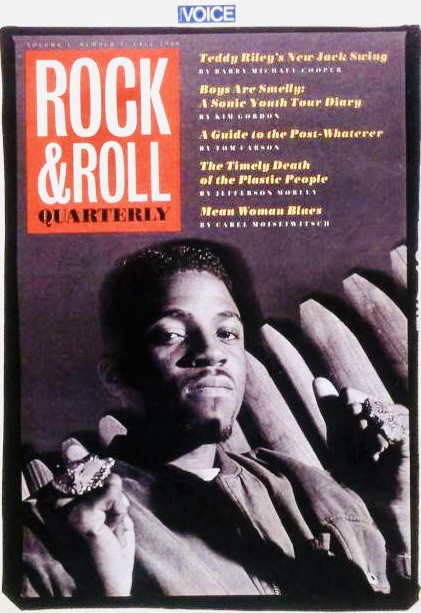

Let’s go back to 1986…I was like around 27 or 28 at the time. I was trying to make a lot of traction at the Village Voice, because I wasn’t a staff writer as of yet. I was the first young black writer there before Nelson George and before Greg Tate. I wrote the published piece on hip-hop back in 1980. And it was a piece called “Buckaroos of the Boogaloo.”

That title was taken from a song by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five.

At the Village Voice, I really wanted to take the music, the culture, and the world that I lived in – in Harlem – and bring it to the pages of a really powerful alternative newspaper that got a lot of attention. And I really wanted to follow my passion for investigative journalism. However, it was really hard for me to make that happen for whatever reason, and a lot of it had to do with the the politics that were already established at the Village Voice.

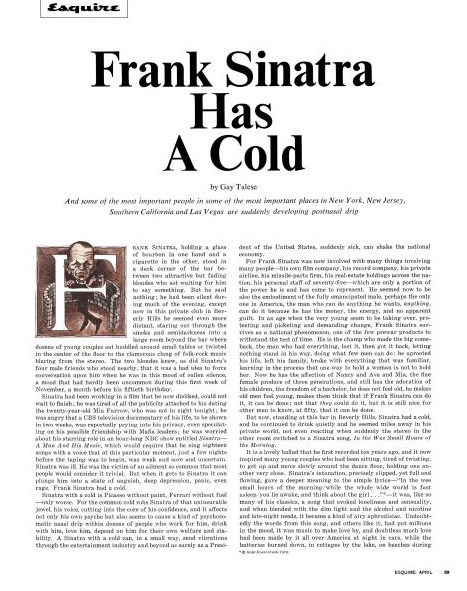

So, I did a lot of wood-shedding. I did a lot of reading, got into an earlier movement of journalism two decades before me called New Journalism with Tom Wolfe and Gay Talese and his great story that he wrote in Esquire Magazine called “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold.” The thing about New Journalism is that this new pop culture in the 1960s which created Cassius Clay who became Muhammad Ali, that created Andy Warhol, that created television, that created Rudy Gernreich and Twiggy – it represented a breath of fresh air from the repressed 50s. Of Eisenhower and the communist scare, and all of that stuff.

It was “do your own thing.” It was Dr. Timothy Leary: “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” The LSD craze. All aspects of that ’60s culture from art to even journalism reflected “me-ism.” It reflected a spirit of, I’m not holding back anymore. And so this whole school of new journalism fascinated me because I said to myself, that’s what I want to do with this culture of what Andre Harrell now calls “Ghetto Fabulous,” in Harlem.

I grew up around a lot of drug dealers. I even used drugs from the ages of 14 to 22. I never sold them, but I was in the environment. The heroin dealers in our neighborhoods – we called them scramblers, because the way they mixed the chemicals, it looked like they were scrambling eggs – they had a certain kind of music, they had a certain way of dressing, speaking, it was a movement. My thinking was, this is my way of making a name for myself in the Voice.

You see, the Village Voice came at writers like, what’s your shtick? For example, Greg Tate – one of the greatest writers I’ve ever read – he had the “Black bohemian” shtick. Then you had Nelson George, one of greatest critics I’ve ever read, and a pure writer – he had the, “I’m gonna be the black or the young Stanley Crouch” shtick, where he’s just this really incendiary critic who also, was very knowledgeable about the subjects that he took on. I wasn’t as strong a writer as Greg Tate or Nelson George, but I knew the world that I lived in. They were aware of it, but they didn’t know it as well as I did.

So, I wanted to take this street world, this underworld, and bring that to light. I was especially inspired to do so after reading Gay Talese’s “Honor Thy Father,” which was a real life account of a real mafia family – the Bonanno family from New York to Arizona. And also the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald, and everything that he did.

Now “New Jack” was a term that I heard the MC in the Cold Crush Brothers, Grandmaster Caz used on a song. And it really was a derogatory term. It was like, this guy’s a new jack. He’s a wannabee. This guy is not the real thing, he’s not the genuine article, he’s a wannabe. And he called some guy on one song a new jack clown. I’ll come back to that.

By the mid 1980s, because I had moved to Baltimore (to get married and raise a family), I became sort of out of the loop on Harlem and everything that was going on at the time with crack. I remember my younger brother Brent, who was still out there called me up one time and said, “look man, when you get a chance go to the library, pick up the New York Times, there’s this piece that happened about this crack thing.”

He then told me about a guy who we grew up with, who took his bike to a crack house and was never heard from again. My brother was a bike messenger at the time. This was 1985. And I’m like, “he went to a crack house? What’s that?”

He responded, “remember the thing with Richard Pryor where he almost got burned alive? Well that’s freebase. There’s an even cheaper form of freebase and it’s called crack. And it is ruining Harlem, and it is taking it over. Every other day there’s a crime going on. Somebody get stuck up, shot, whatever. Girls that we grew up with who went to catholic school that used to be the paragons of decency and virtue – they’re giving blowjobs for $2! Broads you wouldn’t believe…”

So my angle on this new scene was, “this is how I’m going to get back into the Voice. Because they don’t know anything about this.” And at the time they were in such disbelief, saying, “aw, that’s not going on,” so then I went to Spin magazine and wrote the first national piece on crack cocaine.

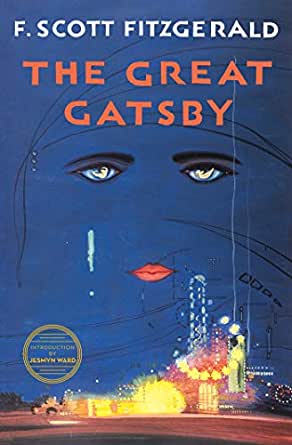

I recognized this epidemic as evidence of a new subculture. One born out of tragedy, but a new subculture nonetheless. One in which serious money was being made by the crack dealers. These upstarts at the “money game.” These “new jacks.” Members of the underclass monetarily joining the overclass. This paralleled elements of The Great Gatsby and The Jazz Age.

To replace speak-easies, they had crack houses. Not to say they had parties at crack houses, but the kids that ran the crack houses, they got their money and then they’d go down to places like The Silver Shadow or Bentleys and throw these parties. I’m talking about young kids in Harlem World on 116th street which is a CVS pharmacy now. These guys would go there with these very thick gold chains, and they didn’t dress like Run DMC. They dressed more like Big Daddy Kane – they were more elegant. They wore the Bally shoes, when Slick Rick says:

“Yo Doug, put your Bally’s on”

and Doug E. Fresh says,

“I wish I could, but I need a shoe horn/

’cause these shoes always hurt my corns.”

“Six minutes, Six minutes, Six minutes, Doug E. Fresh you’re on.”

Those lyrics were taken from real life. These drug dealers had a lot of money, and their cash crop was crack.

Now there’s a political timeline to this. You’re talking about when Reagan took office, and he closed all these programs in the inner city out in Chicago, Harlem, Baltimore, Washington DC, Los Angeles – every major urban center where you could go to an afterschool center or play basketball or learn how to play chess, or write, get into a writing workshop – that stuff was gone.

So the new babysitters became the street corners, and a lot of these kids who became crack dealers were not dummies. Some of these kids were on the honor roll. When Carter was President, practically every black person I knew between 1976 to 1980 had a job, didn’t want to sell drugs. And among that circle, you would shy way from the people who sold drugs, and even the guys who were selling drugs, were embarrassed to be selling drugs! But that all changed in 1980. And it happened when Reagan took office. That’s why Wesley (as Nino Brown) says in that movie, “you gotta rob to get rich in the Reagan era.” These guys were “new jacks” – people who were the next generation. And that generation happened to be the crack generation – the 1980s.

The term “swing” came from me making the analogy between the music played at the speak easies of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s time to the crack-houses of Teddy Riley’s time. These guys made exorbitant amounts of finance and they would spend it in these clubs, and on cars, and on girls, and on champagne, and on gold chains, and on custom-made shoes from Bennis Edwards up on 51st street.

I have to make this important point: these guys weren’t dressing like Run DMC. With those guys – I don’t want to call it cartoonish because I don’t want to belittle DMC and LL Cool J, but it was the Queens version of the high life. But when it got to Harlem, it was like, David Levering Lewis’ book, When Harlem Was In Vogue and those great James Van Der Zee photographs of these people and these mink coats in the ‘30s man. On Striver’s Row in Harlem – Teddy brought that back. He brought back an elegance.

NJS4E: So, if I were to sum it up, could I say that the “New Jack” part of it comes from that aspirational quality, that drive to succeed economically no matter what? The desire and accomplishment of becoming nouveau riche?

BMC: You nailed it, that’s exactly what it is.

NJS4E: So this new edgier, hip-hop/R&B hybrid that Teddy started, was this the soundtrack to the “Nino Browns” of the world? Was this the soundtrack to those dudes who were selling the drugs but making all that money?

BMC: Absolutely – you nailed it again. It lent itself to the whole aura of Teddy’s elegance, and Gene’s elegance.

The first time I was at his home studio up in Riverdale I was blown away. Riverdale was a part of the Bronx that was like Beverly Hills: it was exclusive, it was secluded, it was quiet, it was clean. So I’m at his home studio watching this guy play keyboards, I’m thinking oh stuff, this dude can actually play! He plays like a virtuoso. It’s not two fingers picking out stuff really well, I’m talking about fully fingering the keyboard like Van Clayborn. That’s the first thing that blew me away.

Teddy’s music – the “new jack swing” was fascinating because it was very complex music – it mixed so many seemingly disparate elements together. The thing about Teddy – I called him a modern-day Mozart in that Village Voice piece – he was into composition. Composition is everything whether you’re Basquiat or Picasso, whether you’re Richard Wright or F. Scott Fitzgerald, or whether you’re Francis Ford Coppola or Spike Lee or Robert Townsend. How you compose whatever you’re trying to convey to the audience, will speak volumes as to how they will understand it. And so that’s what Teddy was doing: taking elements of Prince, and Sly, and Marvin Gaye, and Beethoven, and go-go music from DC, and hip-hop.

When I first heard “I Want Her” by Keith Sweat, oh man. I’m not a dancer – I’m a big fat guy. And I wasn’t that fat back in 1987, but my little sons who are in their 20s now, were looking at me saying, “oh Daddy’s dancing, I’ve never seen Daddy dance before!”

When that thing came on the radio Andrew, it was crazy – it made me feel like I was a teenager again. It was like going to a P-Funk concert. “I Want Her,” – the way he would use the keyboards, the way he delivered the breaks, the pauses, the coda, the arpeggios … this guy was a true musician in his DNA.

So yes, New Jack Swing was the soundtrack to the Nino Browns and Gee-Moneys of the world, but it was more than that: it was a very elegantly composed soundtrack also, about their lives.

Editor’s Note: when listening to a song like Guy’s “Piece of My Love,” (there’s a few things in my past, that should not be explained) it becomes fairly easy to see how a drug dealer could relate to the lyrics. A fast life that alternated between parties and girls. This was the life of someone after the high life – at all costs. Bobby Brown’s “My Prerogative” (why can’t I live my life, without all of the things people say?) could fall in the same category. A self-centered, unabashed “me-ism” that is arguably at the root of all capitalist ideology.

NJS4E: One of the things that inspired me to create this website was that I felt that there really hasn’t been many musical movements that have permeated culture as profoundly as New Jack Swing did, and has. From the movies, to television, to the style of dress, the way people looked, etc. So I would want to hear – from you as someone who named this genre – what did New Jack Swing mean, maybe between the years 87-88 to ’92, and what does it mean to pop culture now?

BMC: That’s a really great question. I’ve been thinking about that, and what I’ll say is this. Let’s look at hip-hop, and where hip-hop came from. And what people don’t understand is that there are two birthplaces of hip-hop. One is the Bronx and that’s very obvious, and that’s the one that gets the most ink in these books that are coming out now. They talk about the parties up in 18th park in the South Bronx, and Flash and Cool DJ Herc. I remember when I was in high school and Herc used to throw these parties in the Bronx and they threw a lot of parties in Manhattan and Harlem. He would go by the name of Cool Herc or Cool DJ Herc at the Lincoln Project on 135th street and 5th avenue, and there was another Lincoln Projects by the actual Lincoln Center on 65th street downtown. So he would throw these parties.

Now when these parties were in the Bronx, they were really grimy. It was about the stick-up kids, but even then it was still all about the dress, it was not just the music. It was about how are you gonna come to this party? What kind of gear are you gonna wear? Because remember, you’re trying to pull girls too. So how you look – your presentation – is everything, ok? So that added to the mystique, the aura, and it became a cornerstone of this hip-hop music, along with the graffiti and the break-dancing.

But see, people in Harlem were not checkin’ for breakdancing. Their take was, I’m not getting on my neck, and spinning on my head, and messing up my clothes. I’m not doing no shit like that. When it came to Harlem, it changed. Our main hero in Harlem was DJ Hollywood, and he was famous for two reasons. One, he was as good a DJ as Flash, as Grand Wizard Theodore, and as Herc. But the other thing that set him apart, was that he could rap. And he would rap while he was spinning records. That was reason number one. Reason number two, you had to be geared up to come to a Hollywood party, you’re not coming there like a bum. You’re not coming there in no jeans, man.

If you come to a Hollywood party, you’re first going to A.J. Lester’s on 125th street which was this big clothing store, it was really where the drug dealer guys went, but that was your stuff where, you would have to go all the way downtown to 5th avenue or Madison ave to get the elegant clothing like Eve St. Laurent and stuff like that, you could get it at 125th street at AJ Lester’s. So you’re going to AJ Lester’s to get a pair of gabardine slacks with the “W”-stitch over the ass in the back, one flap on the back pocket. You’re getting a pair of British Walkers from British Walker shoe store, it was this suede cool slip-on shoes in different colors with a buckle on the side near the ankle, they were really cool. And you were wearing a Damon-knit Mock-necks: it was an Italian clothes-maker. And you were definitely going to wear some Caron Bain De Champagne cologne. Now that’s how you were coming to a DJ Hollywood party.

It was a different thing – it was a different mindset, it was a different attitude, and there was an arrogance. Within the five boroughs, the sentiment was, them n*ggas in Harlem is arrogant. That’s why we can’t stand ‘em. They called it money-makin’ Manhattan. And we were like that. Because it’s still the ghost of the Harlem Renaissance and James Van Der Zee and Roy DeCarava photos and stuff like that. So that was imprinted in our DNA. We were definitely arrogant.

So that’s how you were coming to those parties. It wasn’t like the Bronx. Not to down the Bronx because they started it. Hip-Hop started in the Bronx. But it became glamorous in Harlem. So, Teddy took that, he took that culture, and when it got to MTV and BET, people not only in Harlem, but in Philly, ok, and DC where they were already high-fallutin’ anyway, DC sayin’ “we ain’t wearin Gucci, we’re wearing Armani.” Chicago? Great dressers out there. Detroit, Los Angeles. It tapped into a culture of people who didn’t want to be grimy. They were upwardly mobile and they wanted to be affluent.

At the party, they were like, “we know there are some gangsters here, but we’re gonna ignore that. They’re very well dressed, they are very tasteful, they’re wearing a Tag Hauer watch, or a Rolex, and we’re gonna mingle with them. Now when we leave here, we’re not gonna touch ‘em. But when we’re at the party, they got great anecdotes about how they got here. Let’s drink a glass of champagne with these guys.”

New Jack Swing, with its culture and dress code, took away the fear factor of the ghetto which had been crystallized by the Reagan Era and the crack epidemic of the 1980s. It attracted a lot of white people too. Because of the fact that it was upwardly mobile, it had the feel of F. Scott Fitzgerald, of hangin’ out and having a good time, almost like a Studio 54-ish, disco thing. You were going to hang out and rub elbows with the glitterati. Oh, and it made Black people look good!

Now I gotta be frank, and I’m not trying to put a racial spin on it, but if you get to the core of it, it made Black people feel really good about themselves in an era of Reagan, an era when Black people were being vilified, and basically made to look like monsters. NJS created an era where Black people could go out and have a good time, dress nice, and enjoy themselves, and at that time nobody was getting shot? The success of that culture was a no-brainer.

So, when New Jack City came along, that blew the doors off of it. Because that was the biggest, 90-minute commercial that Teddy, or anybody else could have had of that music and that lifestyle. Between Wesley’s performance, and Chris Rock’s performance, and Allen Payne’s performance, and the amazing job that Mario Van Peebles did directing that movie, that was a huge commercial for the movement. A commercial that turned into, and not patting myself on the back, a classic piece of filmmaking at that time.

People were overwhelmed by what crack did to their neighborhoods. New Jack City answered a lot of questions for them. They understood it. There was a face – they put Wesley’s face as Nino Brown, as the crux of the problem. Oh, now I get it. Now I know why the street corner is gone. Now I know why my daughter or son is out there like that. They understood it. It put a face and a name to this problem that had come out of nowhere and overwhelmed everybody.

So to have all of this cultural context mixed in with the music, you’re right – there’s really been no other culture like that. And it’s still here to this day, they just call it ghetto fabulous. Between the Neptunes, and Jay-Z, and Nelly, and all that bling we hear about now. And then there’s that collective out of New Orleans calling themselves “Cash Money.” So obviously the New Jack City film reached them too. Justin Timberlake is definitely a New Jack Swing kid. Britney Spears even re-did “My Prerogative.”

The great thing about what you’re doing Andrew, and your website, is you’re identifying what it is. People don’t know what it is. They see it all around them. And they know about it. New Jack City gets shown ad infinitum on Black Starz network and Cinemax and HBO, and subconsciously they understand it, but you’re really identifying it, putting it in bold, ital, and underlining it for them. So, that’s what the culture represented.

After New Jack City I remember when Andre Harrell approached me, saying “I want to take Ice-T, and Mario’s, and Judd Nelson’s character, and make a TV series,” but foolishly, I turned him down, as I was working on another film project. However, Andre went to Dick Wolf and he did it – New York Undercover. So that carried New Jack Swing past its initial 15 minutes between ’87 into 92, beyond into the late ’90s. Meanwhile we’d also gotten to Puffy and Biggie – they took it even further. Then Jay-Z. There are so many songs between Puffy, Biggie, and Jay-Z where they name check Nino Brown. They talk about it. Andre and them at Uptown called it Hip-Hop/Soul, so it was a little different, but Teddy created that movement. Teddy created it.

And now? You’re just identifying it. As a matter of fact, in a few minutes? Yo…this whole New Jack Swing thing that you’re doing? It’s gonna be bigger than Hip-Hop. It really is. Once they understand what it is, if not bigger than Hip-Hop, just as big. And it’s gonna be an off-shoot of Hip-hop that grows into what I call the “Vanity Fair/Forbes magazine” readership. Because then all of the sudden, Beyonce, Jay-Z, and now even Jamie Foxx – he’s a New Jack Swing guy – it’s all there. That’s the new Hollywood man, it’s New Jack Swing. They don’t realize it, but that’s what it is. That’s exactly what it is.

So the culture of New Jack Swing was dangerous, but it was sexy. And people like sexy and dangerous, they like to be scared, and they like to be aroused. That’s why it has sustained itself for almost 20 years.

To me, Hip-Hop in a way has leveled off. Because once pop culture can eat enough, and replicate what’s going on, they don’t need you anymore. But they don’t understand New Jack Swing. They don’t understand its an amalgam of the larger society created over the past 50 years. New Jack Swing is Hollywood, its glamorous, its Americana in terms of the music, its partly born out of tragedy with the whole crack epidemic, its speaks to so many different things. Once you can’t nail something down, then you need it – that’s how it is in Hollywood. If they can’t recreate it, then they need to go to the source and they love it when they can’t nail it. They love it! That’s why NJS4E is going to grow by leaps and bounds.