NJS4E: The last time we spoke, we focused on the etymology of New Jack Swing, as well as the culture, sociology and musical roots behind the music. So I think the next logical step would be to go ahead and talk about your personal relationship to New Jack Swing. Why did you latch onto this new form of music with such vigor and such passion?

BMC: I latched on to Teddy because of the fact that I initially wanted to create music myself.

For me, the dynamic was almost like that of a coach or professor observing a truly gifted student. Take for instance, a professor of film at Columbia, NYU, USC or UCLA. That person may have been, in his past, prior to going into academia, a screenwriter or director who didn’t hit the mark. They didn’t have what it took to get to that level, but they learned enough in the process to disseminate that information to students and therefore, they could live vicariously through the success of their pupils. Like someone who was teaching Francis Ford Copolla, Martin Scorcese, Robert Townsend or Spike Lee.

I felt the same way with Teddy.

1980 was a really artistic time – number one because of the fact that music was changing over. So-called disco was dead, but it wasn’t dead for me because I loved disco music because like NJS, it was not just a music, there was a lifestyle behind it. So disco for me was being a young teenager in Harlem going to hear DJ Hollywood, or going down to the big clubs like Pegasus or Silver Shadow or Leviticus and just basically coming into your manhood. It was almost like a rite of passage.

During that time it was about all about Chic, Cameo, P-Funk, Earth Wind & Fire, and these off-shoot groups that came up afterwards when Chic kind of peaked. And then people like Kashif and Prince came along. And then electronic music was really coming into its embryonic stages of popularity through a group like Kraftwerk.

So it was basically a situation where you could create sounds and orchestrate music without formal music training. Not to say that the music was always that great, but it meant that a layman had a chance. You didn’t even need to know how to read music anymore or get trained on an instrument necessarily. If you had a somewhat decent ear, and you could hear differences in pitch, then you could put together songs. So that whole time between I would say between 1980 to 1982, I really wanted to get into music, and that’s what I did with the whole Micronawts project.

Editor’s Note: you can check out one of the Micronawts songs called “Let’s Smurf Across The Surf” here

I was at the Village Voice at the time, and I was exposed to a lot of what they call New Wave and Punk. I would go to a lot of the clubs downtown like the Mutt Club, and there were a few other spots – Max’s Kansas City, and so on. I wanted to get into hip-hop but I wanted to do it differently. I was not a rapper, I was not a singer, but I loved different kinds of music, especially Sly Stone, Herbie Hancock, Prince, and Marvin Gaye.

I had gone to a few Kraftwerk concerts and was just knocked out by how those guys got down. Because their music was, for all intents and purposes, electronic R&B. Before they even got to that big album Computer World which spawned what Afrika Bambaata and the Soulsonic Force did with “Planet Rock,” their keyboard stylings and their beats moved me even from their stuff as early as 1977’s Trans-Europe Express.

So my friends and I went into the studio and I had this idea of taking a P-Funk thing, a rap chant which went “ticki-ticki-ticki-ticki talk y’all,” this bass keyboard and this orchestral keyboard thing to created a song. I recorded it with this Jamaican cat named Smitty, he had a place called Forward Records in Harlem on 144th street and Amsterdam Ave. Smitty was in the mix with Grandmaster Flash, and a lot of young kids in our area who were trying to get into hip-hop.

So how did all that lead to my latching on to Teddy Riley and New Jack Swing? When I first heard his keyboards, I felt the similarity between what I tried to do and what he was doing. So I felt that Teddy Riley for all intents and purposes was like a kindred spirit. He was like, carrying the torch of what I was trying to do seven years earlier, but wow. He took it to a whole other level.

NJS4E: Could you talk a little bit more about your relationship to the Village Voice?

BMC: Sure. It started in 1979…but I’ll provide you with a little background.

I was a news junkie because of my parents. My dad especially. He always stressed to my younger brother Brent and I the importance of communication and being informed at an early age. I can remember when Malcolm X was assassinated – we lived in Harlem, but initially we lived in an area in Manhattan called Lower Washington Heights and up the street from us was a place called the Audobon Ballroom. That’s where Malcolm X was assassinated and I remember when it happened, that was probably the only time I ever saw my father cry. He was stretched across the bed, and my mother was trying to console him and I’ll never forget that day. And from that point forward I remember when I was in 8th grade, my dad gave me some money – it was for a book fair at my school – Frederick Douglass IS-10 Intermediate School, and he said,

“I want you to buy The Autobiography of Malcolm X.”

So I went and bought the book and offered it to him but he said,

“No that’s yours. And you’re gonna read it. And you’re gonna write a book report for me – not for your school, but for me.”

I’ll never forget that man.

And so, I said all of that to say that I was always attracted to news, to information, and to writing at a very, very young age. So when I was in high school I started reading the Village Voice because I noticed that as I spoke about last time, it really carried on the tradition of New Journalism. It was like a no-holds barred thing. I didn’t feel that I had a shot to get into the New York Daily News or the New York Post, or even the New York Times. Possibly, the Amsterdam News where my good friend Nelson George started out as one of the best movie critics in the country at a young age. Nelson – that’s another story in and of itself. This guy was one of the best movie critics along the lines of a Roger Ebert. And I’m not exaggerating because he’s my buddy. This guy could really write at like 19, 20 years old. Really concise, expert cinema reviews.

But I wanted to do something different. I wanted to write about P-funk. This is not a racial thing or anything, but I’d read a lot of the white guys try to write about George Clinton and Bootsy and that whole thing – and that was their take on it. However, I was getting high to this stuff! I was smoking weed to this stuff. I was droppin’ acid, sniffin’ coke, and smoking dust to this stuff. Mind you, I stopped getting high in 1980, but when I was getting high, and I saw these reviews, I thought to myself, they don’t understand it like me.

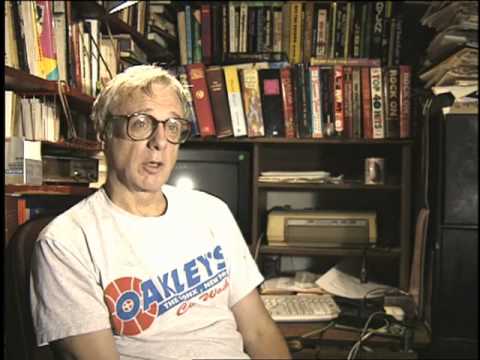

So one late night in 1979, I called up the music editor at the Village Voice, the famed Bob Cristgau – they called him the Dean of music critics – and woke this guy up outta his sleep. He was like, “who in the eff is this?”

And I said,

“My name is Barry Cooper,” I didn’t use my middle name at that time, “I’m going to school at Medger Evers College. I’m sorry to disturb you but I just wanna tell you that your paper’s review of This Boot Was Made For Fonk-N, was good, but I can write better than that. I get high to this music.”

He said, “who the f*ck are you? Who are you?”

After a few minutes he was like,

“Look, bring your piece down to the Voice” – he gave me the address, and said, “if it’s good, I won’t call the cops and report you for harassment. If it isn’t, you’re gonna have problems.”

To this day, I don’t know whether he was serious or not.

This all took place on a late, late Thursday or Friday night. I went down there on a Monday, and that was my first piece that ran in the Voice – January 10th, 1980 – “The Gospel According to Parliament Funkadelic.” And then right after that, or a year after that I had the first hip-hop piece in the Voice called “Buckaroos of the Boogaloo,” and that was either 80 or ’81 and I know it was the first one.

So I was the first young, black music critic there at the Village Voice. I planted the ‘explorers flag’ for Nelson George, for Greg Tate, and everybody else that came afterwards.

Music criticism is a grind, and unless you really enjoy it or you’re as a great as this young guy who writes for the Times now, Kalif Sena, this is a real grind and you either want to move up, or you wanna get out of it. I wanted to move up into becoming an investigative reporter, and a lot of what happened in Teddy’s piece is not just a music thing. People gravitated towards that piece because it became a lifestyle piece and it really was a character study of Teddy and his world. So it wasn’t just, “OK, this music is great, I’m gonna call it NJS,” – it was an examination of the elements that created that genre and that movement.

NJS4E: In the first interview you had mentioned that you had gone out to Baltimore, and it was while living there that your brother had called to tell you about the crack epidemic destroying old friends back in NYC. What prompted the move to Baltimore in the first place?

BMC: I left New York to go to Baltimore to get married, and that was back in ’84. But I was kinda back and forth between Baltimore and NYC, seeing if I could get a shot at this magazine or that magazine and then I would stay in Baltimore and work a regular job. In hindsight, I was really going about it the wrong way because when you do a really good story, you have to have a kinship with the subject matter. And my subject matter was the street, because that’s what I came up in.

I was an oddball kid, I had one foot in the library, reading James Baldwin, and Richard Wright and Dovsteyesky, and one foot in the street. But I didn’t feel that I belonged to either world, so I tried to fuse both. And when I understood that, that’s when I said, this is what I wanna write about – the street. No one’s writing about the street right now. They see it happening all around them, and they’re ignoring it. But something is telling me that here on the street corner, here in the city is where the world is gonna change.

And it did. The music world, the politics of this country, the culture of the country changed on the street corner. And once I understood that, when Brent told me about this guy we group up with, taking his bike to a crack house, and I asked what a crack house was, that was an epiphany. That was it.

NJS4E: My next question goes more towards your involvement in film. How did that relationship come about?

There were a lot of twists and turns leading up to it.

All I wanted in 1986 to 1987 was to be on staff at the Village Voice and that didn’t happen for whatever reason. It was all about cliques and camps, like a big high school almost. But I got a shot by an editor at the Village Voice named Rudy Langlais, who eventually went on to produce my movie Sugar Hill. He produced Redemption: The Stan Tookie Williams Story starring Jamie Foxx, and executive produced The Hurricane starring Denzel Washington.

Rudy initially brought me into the Voice and said, “you should be doing bigger features instead of just music criticism,” and gave me this assignment on Frankie Crocker, the legendary late disc jockey out of New York which I did, but the Voice never ran the piece.

So I continued to work on my craft.

I spent a lot of time in the library just reading everything I could get my hands on. Especially, I was drawn to Dostoevsky. I read a piece by Richard Wright called “The Man Who Lived Underground.” And it’s a great story because you never know the guy’s name – it’s this black guy in Chicago who is not accused of a crime, but thinks he accused of a crime, and goes into the sewers of Chicago, escaping the cops who are not even after him, and he comes up through one of the sewers into this factory building if I remember the story correctly, and gets to a typewriter and writes his name in lower caps “fred daniels,” and that’s the only time you know his name. And when I read a story by Dostoevsky called Notes From Underground, I recognized that Wright was influenced by that.

It was that thing … going back to classic writing and literature, where I found my voice.

So then Rudy told me about this guy who is a good friend of mine and a mentor, Dr. Carl Taylor, a professor of criminology at Michigan State University and at one time, a bodyguard for Michael Jackson. Like me, he was an oddball: he had one foot in academia – he was this big time professor of criminology, but he was also doing security work. So I got to meet Carl and he had this story about this drug cartel – one of the biggest in the country at the time in Detroit by the name of Y.B.I. – Young Boys Incorporated. That story became “New Jack City Eats It’s Young,” and then, Quincy Jones saw it.

This is so crazy man. I mean, one day I’m sitting in the writer’s cubicle with Nelson George and Greg Tate and we’re sittin’ all around and shooting the breeze, and I get a call from Rudy Langlais and he tells me to meet him at the airport the next morning. And I said “why?” and he says, “we’re going to Los Angeles.”

So I go to JFK airport, fly out to LA and in the next 24 hours I’m sitting in Quincy Jones’ den with Rudy, the late George Jackson, producer of New Jack City, Quincy Jones, and the late great editor and director Hal Ashby, who directed Shampoo, A Million Ways to Die with Andy Garcia, and also The Last Detail with Jack Nicholson, but this guy is a Hollywood legend. The way it all happened is still overwhelming because I didn’t expect it. They say God works in mysterious ways, and that’s really true because I didn’t expect for it to happen like that, and then once New Jack City happened, then I sat down and wrote this movie called Sugar Hill.

Above The Rim wasn’t my idea, it was the great, the real life idol-maker Benny Medina’s vision. Now let me talk about Benny for a second: this is the guy who really created the careers of Will Smith, Jennifer Lopez, Sean “Puffy” Combs and now Kanye West. He also truly engineered the comeback of Mariah Carey. Mariah Carey can give all of her latest Grammys to Benny. Benny engineered that. Benny to me, is the most powerful guy in Hollywood.

Well, he and his writing/production partner at the time, Jeff Pollack had a show called The Fresh Prince of Bel Air. And I knew Benny from meeting him at a few Hollywood parties and his giving me music videos to direct. He told me, “look you write some nice visuals, man….you need to be a director.”

So they brought me on.

Overall, those three movies were a great education and it was a life-altering experience. And it was all because of that Village Voice article “New Jack City Eats Its Young.”

NJS4E: So in essence, you were freelancing with The Village Voice?

Yes, The Village Voice and Spin magazine. My star really began to ascend not with the Voice initially, but with Spin because I wrote the first national piece on crack cocaine. It was just called “Crack” and it ran in either 1985 or ’86. And then I wrote a piece that won two journalism awards, it was called “In Cold Blood: The Baltimore Teen Murders.” And that happened at the same time that David Simon was writing his piece “The Corner.” But he was writing for the Baltimore Sun which was like the Baltimore version of the New York Times and he got a book deal out of that. So he kind of overshadowed what I was doing, but I got a lot of press also.

I was supposed to be on The Today Show, but Bob Guccione Jr. was a big ham, and didn’t want to give his writers props and called up there talking to Bryant Gumbel instead that particular morning. But my piece won the 1987 National Journalism Writing Award from Ball State University and the 1987 Feature Magazine Award from the National Association of Black Journalists – that one story. So that kind of got the Voice’s attention, saying, “isn’t that Barry that used to write for us? Get him.”

So that’s basically how that happened.

I had to go outside for them to pay attention to me. And then Spin didn’t want to hire me on staff. So I told the Voice about what became “New Jack City Eats Its Young” and they assigned it to me, and then the piece took off like wildfire. I’m one of the few writers there that had the most cover stories in a two year period. There were only three other writers – there was me, and Playthell Benjamin, and one other writer, that sold out issues with our cover stories.

It all started at the Voice. The movie career really started at the Voice because I was always attracted to drama and cinema, and also great literature. Dostoevsky, if you read Notes From Underground, or The Brothers Karamozov, or if you read Crime & Punishment – those are great visual stories. The directors who’ve tackled them haven’t done a great job of dramatizing it cinematically, but still – Dostoevsky was a great writer and a great inspiration.

NJS4E: One of the illuminating things you talked about earlier was how Benny Medina is someone who is behind the scenes, not so well known among the general public, but has done so much for so many of the icons of pop culture today. Another person I’d like to ask about, is someone the general public may not know, but among the people who do know, he is very significant. And you’re even writing his biography. Can you talk a little bit about Andre Harrell?

Sure. Andre is one of the most savvy, astute, brilliant, cunning, creative record men that ever lived. And you know why? I will tell you exactly why. Andre is one of the few, like Russell Simmons, but even more so I would say, Andre knew when to step out of the mix. He knew when to let Puffy be Puffy, Jodeci be Jodeci, Al B. Sure! be Al B. Sure!, Mary be Mary, Heavy D be Heavy D, and Jeff Redd be Jeff Redd. He knew when to be hands on, and he knew when to be hands off. That’s his great strength. And any manager, or producer, but especially talent manager – if they understand that, will be truly successful.

Ironically I met Andre through the Teddy Riley story. I wanted to get a quote – I can say this now – Nelson told me, “you need to get a quote from Andre because Teddy is on Uptown/MCA,” and I said I thought Teddy was on Motown, and Nelson was like, “yeah, there’s a reason why people think that, call Andre.”

So I call Andre and initially he was a little wary of a reporter calling him. And I said, “I heard a rumor,” and he said, “I knew you were going to ask me about Gene Griffin slapping me around in the offices of MCA, it didn’t happen. We had a disagreement but that didn’t happen and I don’t want to talk about that.”

And he was cordial. He wasn’t abrupt, but did distance himself from the rumors.

When the piece came out, it got so much attention. I mean it was unreal. A week after that piece ran in the Voice, the whole music industry was talking about it. I don’t know why, maybe it was because of the way it was written. Like I said, it wasn’t a music piece, I wanted to apply what the New Journalism did, with Gay Talese and all those people – they went into that world. When Gay Talese followed Frank Sinatra for that afternoon or those two days in that Esquire piece “Frank Sinatra Has A Cold,” it wasn’t so much just about Frank Sinatra and his music, it was about his moods, it was about the world he inhabited, it was about the people he hung out with, it was about his run-ins – had a run-in with a great filmmaker by the name of Haskell Wexler, they were gonna get into a fight at a pool hall. This had never been written about before.

The other thing that made that piece so profound was that Gene Griffin really didn’t talk to a lot of journalists. And the ones that he talked to, he frightened them. He didn’t frighten me. I had a healthy respect for him though, because I knew guys like Gene.

What I told Gene was, “I used to get high. Was that your green Corniche parked in front of that weed spot called the hardest hard on 125th and Madison?”

The guy hugged me. He’s like, “are you sure you’re a journalist?”

I said yeah. Basically I was just like one of them, who just happened to be a journalist. That’s why they accepted me into their world.

So when Andre saw that, and felt that, and knew how important that piece was, and then when he heard through the late George Jackson, “we got Barry Michael Cooper to write New Jack City,” he’s like, “is that the dude that wrote Teddy’s piece?”

After all that, we became fast friends.

And I definitely paid attention to how Andre carried himself. People respected and still respect him. Andre throws people by his personality. It’s really bubbly, he calls his personality “champagne and bubbles.” The guy tells a lot of jokes, he’s funny and this and that, but I’ve learned from the time that I’ve spent around him that it’s almost like a smokescreen to keep you you off balance. This dude is always thinking.

He created Puffy, I don’t care what anybody says. That dude allowed Puffy to be Puffy…he stood back, he gave him a lot of advice, he gave him a lot of knowledge by allowing him to work for Uptown and learn the ropes of the music business, but he basically made Puffy. He made Mary. All of these people. I don’t know what they would say to that, but from where I sit, and I feel that I’m a really humble but very keen observer of the culture, Andre’s a very powerful guy. And his power comes from his generosity.

NJS4E: How would you compare Andre to a Russell, and how would you compare Uptown to a Def Jam? Would you say it was that whole Queens/Harlem thing going on again?

We could talk for days about that, but to kind of cook it down to its essence, Russell comes from Queens. He came from a mom and dad who had really good jobs. He was exposed to the street, but he was also exposed to suburbia. That’s what he grew up in. I remember Russell used to throw a lot of parties in Harlem at City College. We used to have a dance back in the late ’70s called the Freak and the Spank. So he would call these things Freak-A-Thons and Spank-A-Thons.

So, when Russell moved into his prominence, he posted more like a guy who didn’t need the trappings of the fancy clothes and stuff like that. Russell was like, one of the rich white boys in Malibu, you know. He might be carrying an AMEX black card, but he’s also wearing a pair of jeans, a pair of adidas, maybe a polo shirt and a baseball cap. But again, he’s got 2 million dollars on his card sitting in his pocket. However, before I continue let’s make one thing clear: Russell Simmons is really the godfather of this whole thing, if there was no Russell Simmons, there would be no Hip-hop music industry period. There would be no Andre Harrell, there would be nobody.

Andre on the other hand, is from the same mindset that I’m from. Andre comes from a relatively middle class family, but he grew up in the projects and I grew up in the co-op in a place called Esplanade Gardens. Andre had really loving parents like Russell, but his environment was different because it wasn’t the suburbs, it was the South Bronx: the projects, the gangs, the Glory Stompers, the Black Spades, all of that. We wore our affluence on our sleeves, literally. When we got money, when we got our neighborhood youth court checks, mind you, I wasn’t selling drugs, and Andre wasn’t either, we’d go down to 125th street to Tavdash or AJ Lester’s and get the silk pants and the British Walkers, the mock necks, and the champagne cologne, and that’s the way we celebrated the effervescence of having money and being young.

And that carried over to New Jack Swing, which became Hip-Hop/Soul, which became Ghetto Fabulous. So, if Russell is a guy like Jeffrey Katzenberg or one of those high-powered Hollywood types that doesn’t have to get dressed up, Andre is the opposite: he’s Edgar Bronfman Jr., who will wear a very expensive suit with the custom made shoes and the whole nine yards. They took different takes on affluence, but they’re basically the same person.

The other thing is Russell’s thing, to me, had more of a “rock” undertone. The way he approached rap with his first stars – Run DMC, LL Cool J, they were like rock stars. They were hip-hop, not R&B, and they were the first guys to really cross-over and grab that rock audience, especially Run DMC’s “Walk This Way.” Rock was still THE powerful music at the time. Hip-Hop was still in its infancy in terms of its emergence in pop culture.

Andre, he was more Gamble & Huff. He was more Motown. He was more of the elegant, “black” thing. And that created the Teddy Rileys, the Mary J. Bliges, the Al. B. Sures, and people like that. It was an elegant way of looking at the music. That’s the difference to me. Russell was rock, Andre was more Hollywood.

NJS4E: Can you talk a little bit about some of your most memorable interviews?

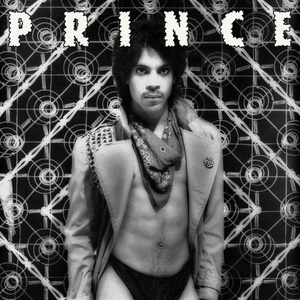

Sure. One of my first memorable interviews was with Prince. That was for a newspaper that’s been long gone, it was called the Soho News Weekly, and it was a Village Voice competitor for a while, but they couldn’t hang, and it morphed into a downtown glossy called Paper Magazine.

That interview was crazy. I really saw how complex this guy was. I interviewed him in New York. It was around the time of the Dirty Mind album, and I had just see him a few months to a year before at a place called The Bottom Line in the Village right across the street from New York University. And he came out with the long hair, and some cheetah-print bikini drawers, and his band did too. That’s when Dez Dickerson and Andre Cymone were in the band with him, and it was nuts man. He killed it.

And I remember the guy who was his opening act was Keenan Ivory Wayans. I’ll never forget that. And he almost looked like, and I hate to say this because he’ll probably snap on me later, but this is when he was going bald at the time, he almost looked like a tall, Bozo with a short afro, it was crazy. He was mad funny though. He did this whole joke about a Puerto Rican Soul Train, and had the whole audience doubled over, including myself.

So he opens for Prince, and Prince kills it, so I remember going to the Voice, pitching the a piece about it to them, but I think they had assigned it to Greg Tate, so I went to Soho News Weekly, and they wanted me to start doing some writing for them anyway. They gave me the assignment it was called “Prince of Darkness,” and I’ll never forget the piece. When the story ran, they had cut out certain parts to make him look almost sinister, but he’s not that at all. Prince is a funny dude, he was really comical. I remember he was wearing the raincoat, and he had a very serious look on his face when I asked him,

“On one of your songs, Sister, are you talking about having sex with your own sister?”

So he answers with a gasface/scewface on, “maybe that voice came from the other side.”

So I busted out laughing in his face. And he said, turn the tape recorder off. And he fell on the floor and rolled with laughter. Then he says, “don’t ever tell anybody I did that,” and then he said, “cut the tape back on.”

And then he went back to the gas face/screwface on.

So it was an act, that was his shtick, being this weird guy. But he was a normal dude man, and so nice and gracious. That’s an interview that stuck out. And I gave him one of these small Bibles, it had Psalms, Proverbs, and the New Testament and he said, “wow, thank you,” and shook my hand so tight. I’ll never forget that.

And then Nelson George – we’ve been friends for a long time – he came to me about two weeks later, and said “you know there’s a guy doing a book on Prince and he wants to talk to you.”

And I said, “oh really?” and he told me that Prince has asked about me.

“What about that fat guy with the glasses?” Prince asked the writer backstage during his first appearance on Saturday Night Live. “I like that guy, what’s his name again?”

So that was a very memorable interview.

Then there was R. Kelly. That was really memorable because, first of all this guy does not go to sleep. He might sleep in 15 minute intervals, but I stayed up for almost two days hanging out with this guy. And it was strange in a sense that I was expecting this bizarre person, and parts of R. Kelly – and this is not an act with this dude – he is really kinda strange. Something’s going on with him. But he’s a real genius.

When I sat in the Chocolate Factory studios and watched this dude play like Beethoven, like really, really play – it was awesome. I didn’t think he could play like that. I had heard things, but I’d never seen him in concert so that was my first time, and there’s nobody like R. Kelly. Like Teddy, he is a real genius, he’s one of those rare people like Stevie Wonder, like Prince, like Todd Rundgren, but he’s tortured for real.

He started crying while he was playing this ‘soldier’s song’ – it was a double entendre about these guys in Iraq and I think the Lord Jesus Christ, I’m not really sure, but I know he started crying while he was playing it. And then right after that, he started playing like he was a lounge lizard, and started laughing. And I said to myself, you know what? It’s either I’m sleepy right now, or this guy is really crazy. It’s either one of the two, and maybe it’s a mix of both.

And another thing that stood out about the R. Kelly interview: he had his studio made up like a jungle with real live plants and trees! When I started walking through the hallway to get to the actual recording studio I noticed that I started having to move leaves out of my face. So at that point, I was saying to myself, I know I haven’t been asleep in 18 hours but I’m moving leaves out of my face in a recording studio!

He said he did that because he wanted to create that effect of being in Africa. He had all these pictures of lions and apes, and these books and maps of Africa…it was crazy man. He explained, “when I get into something I really try to study it and get into it and absorb it. I know I can’t go there.”

I asked him if he was afraid to fly and he didn’t answer that. But his manager Regina Daniels kinda alluded to the fact that I think he has a fear of flying. I think he will fly but it takes a lot to get him on a plane. That was a memorable interview too.

I’ve had quite a few memorable interviews, and not just with music people – from criminals to kids in jail, to people that have killed people, it’s been a ride man. But in terms of how did that relate to what I’m doing now – I think my strength is writing. And even my foray into directing and filmmaking comes from the fact that I love to write. And I think the best stories – if they are solid – can be told via film, can be told on record, or they can be told between the pages of a book. But a great story is a great story. When you can hold a person’s attention – whether its for 10 minutes or for two days, or whatever it is – you have something precious and you can’t waste it. And you have to make the best use of it possible. So that’s what I’m trying to do. Extend my ability to tell a story or to communicate through films and other mediums right now.

NJS4E: Amen to that.

Move on to Part 3

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.